Sourdough Bread at UCCS' Farmhouse

This coming Friday, March 8th (sign up here), we are working with sourdough bread, inspiring attendees to try and give it shot! And if it does not work the first time it will work the more you try. Making bread with 100% whole grain ingredients is a journey that you might never leave again. Perhaps more than anything, starting to dive into this grain journey is about taking the time to learn something new- something essential that feeds us, something beautiful that inspires us, something sacred that brings us together, and something quite difficult that challenges us. Artisans take this work very seriously – be it in growing the grain, milling it, or working with it in the bakery and transforming it to the staff of life - bread.

Real whole grain sourdough breads have disappeared from our grocery shelves and from our lives. It’s only through the revival of heritage grains on diversified family farms and professions, such as artisan bakers and millers, that these breads are now reappearing. Sourdough fermentation in breads (and beer!) probably first happened by accident. But it is thought that this type of bread making probably dates back to the region of Göbekli Tepe in Southern Turkey, close to where wild einkorn – the first domesticated wheat – was found around 10,500 years ago. For more information on Einkorn’s fascinating story click here.

Sourdough bread, especially made with rye and barley, traces back to ancient Egypt around 1500 BC. Sourdough starters, also called wild yeast, are made without commercial yeast. They take time and integrate the microbes of your home, your hands, and nature around you. A project by the Rob Dunn Lab is currently investigating how bakers are linked to the sourdough starters they use to make bread. As you can imagine, microbes in the environment can directly interact with the microbes in our bodies, potentially contributing to diversity, for example in the human microbiome. While research is clear regarding the positive impact of sourdough-fermented bread on digestibility of grain and bioavailability of nutrients, the question, why so many people react negatively to wheat and bread, remains unanswered.

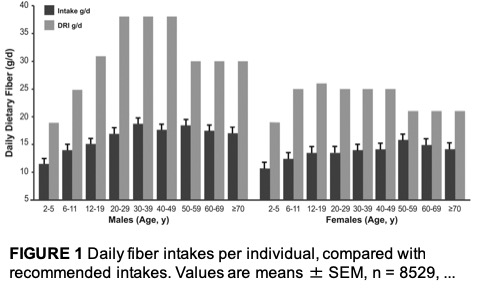

The integration of whole grains, especially coming from regionally adapted grains and the nutritious heritage wheats, rye and culinary barleys is nothing short of impactful for human health. There is good evidence that whole grains, and specifically dietary fiber, reduce mortality and the risk of diet-related chronic diseases, such as diabetes, heart disease, and colon cancer. Recent research confirms a significant fiber gap in diets around the world, but especially in Americans.

FIGURE 1 Daily fiber intakes per individual, compared with recommended intakes. Values are means ± SEM, n = 8529, estimated from Day 1 dietary recall interviews conducted in What We Eat in America, NHANES 2007–2008. The 24-h recalls were conducted in person, by trained interviewers, using the USDA 5-step Automated Multiple-Pass Method. Food intakes were coded, and nutrient values were determined using the USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies 4.0, which is based on nutrient values in the USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 22. Intakes of nutrients are based on the consumption of food and beverages and do not include intake from supplements or medications. Mean fiber intakes for individuals aged ≥2 y do not include breast-fed children. Data are from (7, 13).

The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 142, Issue 7, 30 May 2012, Pages 1390S–1401S, https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.112.160176

Because grains make up at least 30-50% of our total daily intake (and up to 80% if we count the animals we eat also being fed with grain), it seems critical to make the most of these grains by eating them whole and intact, to ensure we get all their nutrients. Whole intact grains are an excellent source of carbohydrate, protein, fiber, B-vitamins, essential fats, polyphenols, and minerals such as iron and zinc. Removing their bran and germ means this nutritional benefit is lost. As for fiber, a slice of whole grain bread has 5 times as much fiber than a slice of white bread.

During the modern process of milling of whole grain to white flour, the grain basically loses its fibrous coat and oily, nutrient-dense core and what’s left is empty flavorless starch. Because the grain in this state is nutritionally depleted it ends up being enriched with vitamins and minerals in order to not cause nutrient deficiencies. This process seems rather silly and is unsustainable, considering the projected increase in population density and climate-related food shortages resulting in the need for people to eat less but more nutrient-dense foods to sustain health and prevent disease.

When whole grain is freshly milled and mixed into dough with water and salt, followed by fermentation over hours and days, nutrients, such as iron, zinc, fatty acids and polyphenols become more available to the body, meaning the food becomes more nutrient dense. The sour taste- hence sourdough- is due to a drop in pH level, which assists in improving the bread’s digestibility, flavor, and shelf-life.

Dating back to the middle ages, sourdough breads had a real purpose – shelf life. Villages had only one wood-fired oven and bread baking was a communal activity and only occurred in monthly intervals. These breads were all made with wild yeast using only whole grains that were freshly milled in water-powered stone mills. That we eat grains processed, without much of their nutrition, is a result of the invention of the roller mill that allowed for separating the bran and germ from the rest of the grain in the late 1800s, making “white” the new norm.

Today, we are gradually returning to whole grains and sourdough breads, with artisan bakeries popping up in most cities. While it will require a cooperative effort to re-establish a local grain economy along the front range, change often comes from building consumer demand and this requires awareness. Experiencing and understanding what goes into an artisan loaf and how to make one is the first step in jumping on-board of this exciting regional grain train and is worth every effort!

There are many ways to make sourdough breads. The best is to select one process! Here is one that uses a levain or pre-ferment, in addition to the sourdough starter. I find this process rewarding as it still produces a sourdough loaf but with a more subtle sour flavor.

First step: Milling

2. Step: Make Your Sourdough Starter!

When making sourdough bread you need a good starter. To build a starter it takes at least 3-4 days. The good thing about a good starter is that it may last you a lifetime if nurtured on a weekly basis. In preparation for Friday, we are making the starters. If you like to make your own, follow the steps below:

- If you can use freshly milled flour. Start the sourdough process on Monday morning

- ½ cup whole grain flour + ½ cup filtered (room temp) water: mix, lightly cover, keep on counter.

- Repeat this process on Tuesday morning, adding ½ part flour and water to feed sourdough (1-2 tablespoons is enough)

- Repeat on Wednesday morning as above. You should see your starter bubbly...and is getting ready to incorporate in your baking.

- Repeat Thursday morning as above. Now we are getting ready to incorporate the starter into the flour Thursday evening and Friday.

- Stay tuned for more information!